To different extents but without exception, today’s free market democracies are being strangled by divisive populist governance structures that focus on short term political gain at the expense of long term social prosperity. The Greenfield project was established to encourage the evolution of democracy beyond the stagnant capitalist and socialist paradigms of the 20th century towards more vibrant inclusive economic systems that can harness science to drive lasting prosperity for all citizens.

In contrast to the complexities of modern economics the pathway to prosperity is very simple, we just need to add three key ingredients to existing governance systems:

The project has employed science and engineering principles to design an economic blueprint that will facilitate a stable transition from parochial industrial economy to global technology economy. The blueprint embodies the aspirations and ethics of modern liberal society without the encumbrance of existing defunct industrial economic theory.

The blueprint is comprised of three distinct interdependent components:

Beginning with the birth of the Roman Republic in 600 BC and Greek Athenian society in 500 BC, democratic society has evolved through two and half millennia of strife into the free market democracies that dominate the developed world today. The early failures of Greek popular democracy demonstrated a need for disciplined governance structures that could temper popular emotion and encourage effective planning and decision making. Despite the best efforts of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, Greek society did not succeed in creating an effective democratic governance system and was ultimately assimilated within the Roman Republic which combined popular sovereignty with an aristocratic senate and monarchy. The great legacy of Greek Athenian society is actually its science traditions established by Plato’s universities rather than its governance systems which are considered by most political scientists to be defunct. Today’s capitalist democracies are the latest evolutionary incarnation of Roman governance and Athenian science.

The Roman Republic evolved in various forms over millennia to eventually form the European aristocracy which colonised the globe from the 15th to 19th centuries and was ultimately broken by science in the form of the industrial revolution in the 20th century. The industrial revolution shifted wealth from land holding aristocrats to industry owning capitalists and triggered two mechanised global wars which destroyed the wealth of the aristocracy and many of the early industrial capitalists. Adapting to shifting capital control structures, Roman democracies evolved from aristocracy to newly formed capitalist plutocracies where political parties representing various capital interests compete for the power to govern under popular endorsement. Under this system the parties control policy through nomination of ministers and the public is given the opportunity to endorse party policy by voting during infrequent government elections. Wealthy capitalists typically weald additional power in the system through ownership of media and funding of election campaigns. Plutocracy is a small step away from traditional Roman democracy towards Greek popular democracy but the governance mechanism remains under the control of an elite party mechanism that is receptive to popular aspirations but not subject to popular mood.

In the early stages of the industrial revolution wealthy capitalists enjoyed complete control over production and government but they did not have the same level of control over the populace that the old aristocracy enjoyed and into this gap in power emerged the worker unions and socialist political parties who used the combined power of the social majority to wrestle a greater share of production profits for workers and social services. The resulting distribution of capital and government investment in public education and infrastructure created a new middle class who drove the engines of industry with their expertise, initiative and purchasing power. Populist capitalism came into being when the middle class began to use some of their new found disposable income to participate in wealth accumulation through entrepreneurial activity and investment in industry and property.

The 20th century has seen science and populist capitalism combine to create powerful industrial economies that have provided unprecedented improvements in quality of life for all of their citizens (wealthy and poor alike). This historical account contradicts popular capitalist dogma which proclaims that investment in innovation is driven by the wealthy class. In practice, outside of investment in existing production efficiency, the wealthy class predominantly invest their large stores of capital in established secure assets or enterprises that deliver the regular income that is required to maintain their extravagant lifestyles. Innovation provides broad benefit to society but it delivers unpredictable returns to the investor and often disrupts existing economic systems and revenue flows to the established wealthy class. That is why blue sky innovation is typically funded by government and the aspiring middle class rather than the highly capitalised wealthy class. An excellent case study for this scenario is renewable energy. With the discovery of climate change in the 1970’s the urgency for innovation in the renewable energy sector has been escalating for over forty years and during that time the wealthy class have not only abstained from investment but actively and very effectively sought to prevent investment in innovation through disinformation campaigns, lobbying and industry destabilisation.

At the dawn of the 21st century we are now entering a technology revolution that will challenge and transform all economies around the globe on a scale exceeding the industrial revolution. The industrial revolution saw large scale implementation of production line manufacturing techniques and human operated machines. The technology revolution will see replacement of the majority of industry and services with autonomous machines. The industrial revolution replaced low skilled, low value labour with high skilled, high value labour to increase productivity and feed global markets but the technology revolution will replace the majority of manufacturing and service labour with machines, eventually shutting the middle class out of high value production. The technology revolution began to take hold in the 1980’s with the commercial uptake of advanced ICT products.

In addition to the challenges presented by automation, technology is increasingly facilitating global mobility of production, creating a an international restructure of production (commonly referred to as “globalisation”). To date globalisation has seen massive movements of manufacturing and service industries from developed to developing economies as industry seeks out lower production costs. The globalisation trend is continuing as improvements in communications create a global market place for service labour. The manufacturing industries that remain in developed nations have employed autonomous robots to compete with the cheap labour of developing nations and remaining service industries now routinely utilise cheap foreign labour behind a thin domestic façade.

Globalisation and automation have disrupted income distribution and productivity within advanced economies with resulting increases in debt and deficits as these nations continue to utilise debt to compensate for falling incomes instead of implementing reforms and adapting to evolving economic conditions.

Large scale automation of industry creates a contraction in income for the general population as production revenues are diverted away from workers to industry owners. The contraction in income leads to a contraction in demand for industry products which in turn places downward pressure on product prices and industry owners are eventually forced to surrender the windfall revenues attained through automation in order to maintain sales. When product prices are lowered, capital flows are restored to the market and new industries will be generated to replace the jobs that were lost to automation. This is the natural cycle that occurs during automation of industry and while it is a bumpy road the final outcome is increased quality of life for the general population and improved competitive position on global markets.

A similar process occurs with globalisation where domestic industry is dissolved in favour cheaper foreign production, but with a very important exception. If the additional imports are not balanced with additional exports from compensating industries, quality of life and global competitive position will be degraded until people can no longer afford the cheaper imports and balance of trade is restored. This scenario presents a problem to local businesses who wish to offshore production and maintain sales into the domestic market because eventually their foreign production will become stranded without improved sales to other economies.

The natural balancing mechanisms for automation and globalisation have been suspended for the past 30 years as increasing consumption borrowing has compensated for natural income contraction and averted the balancing effect of downward price pressures. This scenario arose as tax cuts and deregulation allowed industry owners to inject windfall production revenues back into the economy through debt and asset purchases rather than investment in new industries. So as asset prices and debt have continually increased, industry owners have continued to reap windfall production revenues while extracting further revenues from assets rents and debt interest. And while capitalists have been doing exceedingly well in this situation there is an obvious problem for the general economy; debt and asset prices must eventually peak at capacity to pay rent and interest and when it does peak the economy will face potential disaster as thirty years of contraction are realised with the compounding effect of onerous debt interest, high rents and a hollowed industry base.

In the second decade of the 21st century developed economies are fighting contraction and price deflation through money printing, low interest rates, tax cuts and a range of other stimulatory measures in an attempt to avoid runaway contraction and deflation but to date no measures have been taken to restore the natural cycles of income redistribution that are necessary to facilitate lasting consumption demand. Without the natural correction cycle, globalisation and automation will ultimately have a degrading effect on quality of life and global competitive position and industry will shift to servicing the rich and the poor as middle class incomes evaporate.

Globalisation and concentration of production are redistributing income away from the traditional middle class towards the rich and the poor. As the technology revolution continues to unfold (increasing levels of automation in production) the share of income currently going to the poor will be diverted to the rich.

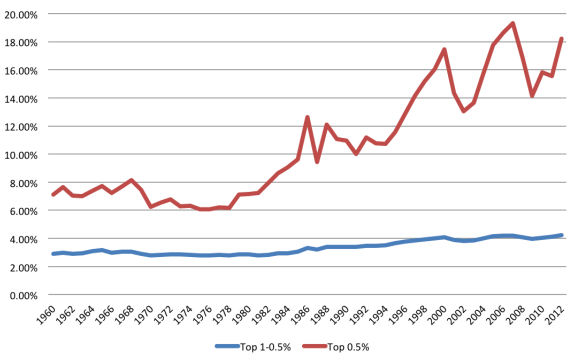

Figure 1 illustrates the change in income over the past 30 years across the spectrum of poor on the left to the rich on the right. The pronounced dip in Figure 1 represents the middle class. On examination of Figure 1 it is important to consider the very small amounts of capital required to create a dramatic increase in the incomes of the poor and the very large amounts required to create a commensurate increase in the incomes of the rich. Figure 2 demonstrates very clearly the escalating income concentrations at the upper end of the global economy.

Figure 1: Change in real income between 1988 and 2008.

Source: Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719.

Source: Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719.

Figure 2: Income distribution for top 1 percent of the global population.

Source: World Top Incomes Database. Managed by economists Facundo Alvaredo, Tony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez

Source: World Top Incomes Database. Managed by economists Facundo Alvaredo, Tony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez

From the beginning of industrial automation and globalisation in the 1970’s debt levels in developed nations have been increasingly escalating while productivity growth rates have been falling. This illustrates in very broad terms that developed nations are borrowing to support their lifestyle rather than borrowing for investment in production. Lifestyle improvements experienced in developed nations over the past 30 years have been largely achieved through debt and increasing hours of labour (as women joined the workforce on mass and the standard working week extended), both of which have now reached peak levels.

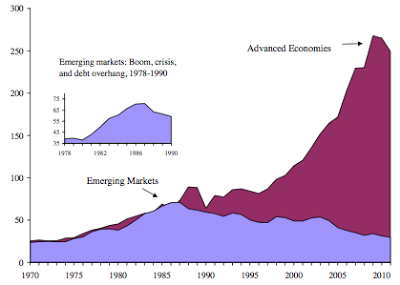

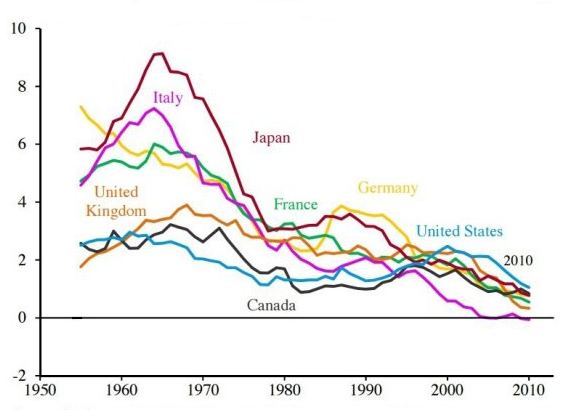

Figure 3 illustrates the stark divergence in debt levels between advanced and emerging market economies while Figure 4 describes the falling productivity rates for the major advanced economies over the same period.

Figure 3:Gross external debt (public & private) as a Percent of GDP: 22 Advanced and 25 Emerging Market Economies, 1970-2011.

Source: Carmen M. Reinhart, Vincent R. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “Debt Overhangs: Past and Present”, Harvard University working paper 18015.

Source: Carmen M. Reinhart, Vincent R. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “Debt Overhangs: Past and Present”, Harvard University working paper 18015.

Figure 4: Figure 4: Labour productivity growth, 1955-2010. 10 year moving average of output per hour.

Source: Conference Board, Total Economy Database; CEA calculations.

Source: Conference Board, Total Economy Database; CEA calculations.

Globalisation and automation are driving fundamental transformation of advanced free-market economies. To harness this transformation and avoid economic degradation a number of key reforms are required to existing governance and macro economic structures.

The plutocracy governance model lacks the rigorous scientific discipline required to effectively respond to the challenges of the technology revolution and it is extremely vulnerable to the manipulations of wealthy capitalists. The conservative nature of established capital is constantly working through the plutocracy to preserve and enhance their economic advantage, often at the expense of broader social interest and essential reform.

Taxes can either be burdened on production or consumption. Taxes on production will increase the cost of local products on domestic and export markets relative to foreign products. Taxes on consumption do the opposite; consumption taxes increase the cost of all products sold into the domestic market without increasing the price of export products. When consumption taxes are invested in science and infrastructure, domestic industry will actually enjoy an advantage over foreign industry on local markets because while foreign products are burdened with domestic taxes, foreign industry does not benefit from domestic investment.

The traditional industrial taxation model places the majority of the tax burden on production through income taxes and duties. This model was effective while global economies maintained similar taxation systems but with low taxing developing economies entering the market, developed economies are struggling to maintain market position and many have begun cutting taxes and subsidising industry in order to compete. The resulting reduction in tax revenue is exacerbating public debt and reducing capacity for public investment in essential infrastructure, science and services which must result in decreased productivity growth and further erosion of competitive position.

Infrastructure costs feed directly into the cost of production, driving up the price of products on local and export markets. Innovation helps to reduce the unit cost of infrastructure but it cannot compensate for other factors such as inflated asset prices and rents, inefficient logistical networks and expensive civic architecture. Over the past century many advance economies (particularly the European colonies) have developed lavish cities off the back of global export profits with little or no regard for efficiency. In a global market place all factors influencing the product price are critical to economic prosperity.

The prosperity of free market democracies hinges on science, leadership and broad distribution of capital. When capital is allowed to concentrate as it is increasingly doing today, the wealthy class divert capital away from consumption and innovation towards stable rent producing assets. This diversion of capital increases the cost of production, decreases demand and reduces productivity growth. As the wealthy class grow more powerful they inevitably use their power to enhance their capital flows and prevent any social change that would threaten them, creating further downward pressure on innovation and productivity. To avoid this death spiral, free market economies must implement constraints on capital concentration that do not interfere with the free market.

The dictatorial workplace structures employed within all free market democracies are designed to exclusively forward the interests of the owners. There are two problems with this model, proliferation of incompetence and opportunity cost.

Opportunity cost is the level of quality and productivity that may be achieved by workplace models that do not deliver optimal control and benefit to the owner. Such alternative workplace models are entirely possible within the realms of free market economy but they are never considered because of the threat they pose to capital accumulation. Owners frequently tinker with the dictatorial model using various worker participation and incentive schemes in an ongoing struggle to improve productivity but they never stray outside the bounds of owner control and net owner benefit.

In organisations where owners are removed from management (such as public service or corporate shareholders), dictatorship nurtures incompetence as managers use their authority to employ workers who reinforce their position rather than threaten it. In such an environment, workers who exhibit competence, initiative and leadership are overlooked in favour of workers who will support and enforce management decisions without question. As each generation of management employs subordinates who are less competent than themselves the quality of management is degraded to a point where the organisation becomes dependent on external consultants for all sophisticated planning and decision making but consultants cannot compensate for an incompetent workforce. The public and private sector in advanced economies is becoming saturated with incompetence as large multinationals absorb and supplant small owner run businesses.

During the industrial revolution the global human population increased seven fold (from 1 billion to 7 billion) and it is still climbing at a rate of approximately 75 million per year. As the overall size of the population increases the growth rate shrinks because the ratio of increase to total volume becomes smaller but the actual rate of increase is still climbing steadily. The optimum level of population for a civilization is not an easy thing to define but it does exist. There is a point where economies of scale that raise quality of life collide with degradation of ecology and diminishing per capita share of natural resources. In terms of natural resources and ecology the optimum population is one, but economies of scale cannot be quantified so precisely so peak scale must be estimated. What is certain about economies of scale is that peak scale will recede with automation of production and all nations have already exceeded peak scale.

With rampant environmental degradation and shrinking economies of scale the human race is facing immediate and ongoing downward pressure on quality of life as population continues to expand. Without remedy it is extremely likely that this pressure will result in increasing poverty, displacement, instability and conflict.

If scientific projections on global warming are even within ballpark range of correct, human civilisation is facing its greatest challenge and its potential devastation. Capitalists with vested interests are playing on the uncertain nature of climate forecasts to argue that no action is required but this argument asks that humanity forego traditional prudence and the benefits of clean renewable energy, in favour of unmitigated calamitous risk and a future of filthy expensive fossil fuels. This is not an argument but fools propaganda aimed at inflaming fear over rational thought.

Insurance is a normal part of capitalist society. With insurance spending in the OECD averaging over 8% of GDP in the last decade, guarding valuable assets against potential destruction is routine economic behaviour. Effective action on climate change has been projected to have an initial temporary cost of approximately 1% of GDP, reversing to a net benefit as the price trend of renewable energy continues its downward trend to become a cheaper and more secure energy source than fossil fuels. When considered against current insurance spending, pre-emptive action on climate change is extremely cheap insurance against potential economic and environmental devastation.

In the past, capital has traditionally combined with some form of political elite to provide a disciplined governance structure for democratic society but the conservative nature of this system is not well suited to the challenges of the technology revolution. In recognition of this situation the zeitgeist of democratic society is moving towards a more scientific and merit based system of government but the existing plutocracy cannot facilitate this transition. Citizens do have the power to reform their democratic governance structures but to do so they first require a clear understanding of the system they are moving towards. The Greenfield Project was established to develop a new democratic governance system and policy framework that will support peaceful evolution from capital plutocracy to scientific meritocracy to harness the benefits of the technology revolution without disrupting the existing free market economy.

The Greenfield economic model prescribes three key structures to create an effective governance system for scientific meritocracy:

The Greenfield Project is a not for profit organisation that is not associated with any political, ideological or commercial interests. The project is constantly evolving and growing with a network of volunteer contributors working to improve and expand the blueprint. All contributions are reviewed to ensure adherence to ethical standards and objective science and engineering principles. To protect privacy and encourage literary freedom, the project does not publish the identity of any contributors.

Please use the links provided in the footer below to provide feedback on any aspect of the project or download a PDF version of the site. Thank you.